BY JOHN FITZGERALD

Part 1

High on castlecomer’s roll of honour is Nicholas (Nixie) Boran.

Boran caused a social earthquake in North Kilkenny in the early 1930s. He was the “Miner’s Friend”, a tireless champion of human rights who followed in the footsteps of Big Jim Larkin. He spread the gospel of trade unionism throughout the county, becoming something of a worker’s Messiah.

His picture hangs proudly on a wall of the SIPTU office in Patrick Street, a testament to his dedicated involvement in the Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union, precursor of SIPTU.

Born in Massford, Mooneenroe in 1904, he was the son of a colliery car man. Growing up in the shadow of the coalmines, he became aware at an early stage of the horrendous conditions in which the miners toiled for long hours and small pay. He read the works of James Connolly, turned to socialism, and swore he’d do everything in his power to combat the unjust and contemptuous treatment of workers in his community.

But Boran got off to a rocky start in his bid to alleviate the plight of miners and quarry workers.

The local branch of the ITGWU had suffered a drastic decline in membership after the unsuccessful miners’ strike of 1926. The miners in Comer were rendered cynical and despondent at the ease with which the bosses had crushed their heartfelt public show of strength and demand for fairer working conditions.

They decided that a new union, with a strong local emphasis, was required to focus on the specific needs of the Comer mining community, the only significant one in Ireland. In December 1930, Nixie Boran stepped into a leadership role in response to appeals from friends, neighbours, and mine workers who had been mesmerised by his fiery oratory and enormous personal magnetism.

They believed he was the man who could release their community from the vice-like grip of Wandesforde, the powerful mining boss in Comer. Together with a few loyal activists, Boran launched the Irish Miners and Quarry Workers Union.

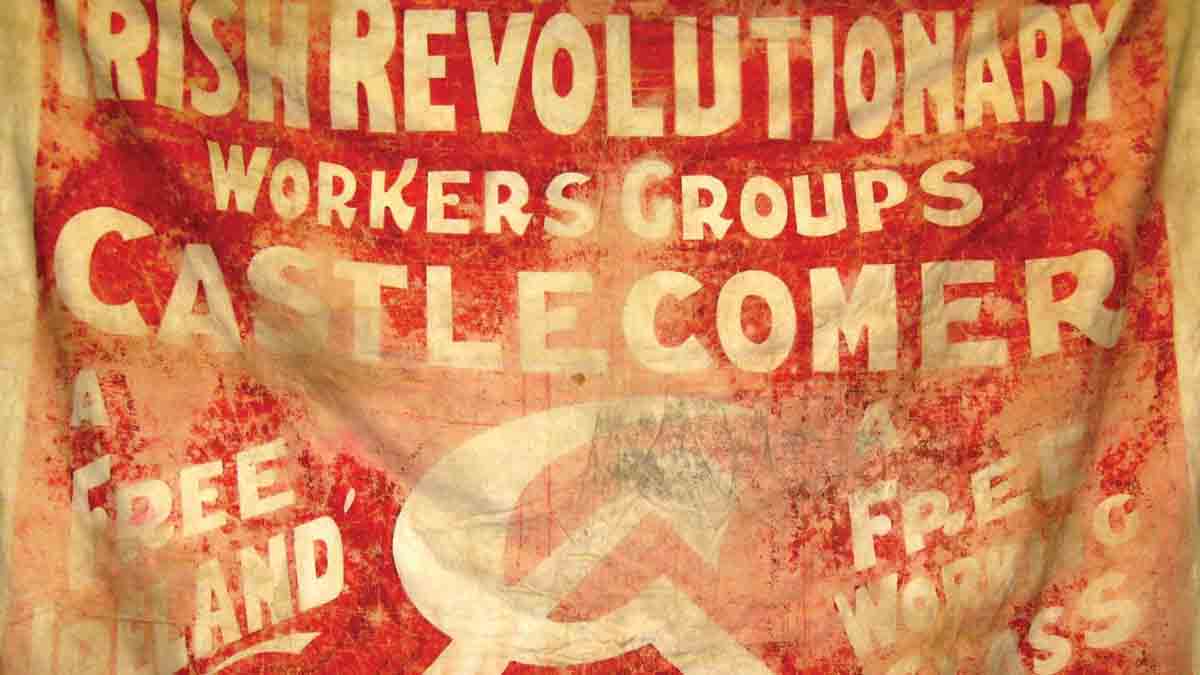

This move sent shock waves through the local establishment. And the bosses were less than pleased by the formation on the same day of the union’s “militant wing”, The Revolutionary Workers Group and the launching of a radical newspaper, “The Workers Voice” to air its views.

What made this breathtaking initiative even more worrying for the bosses was the fact that Boran had just returned to Comer after a three-month visit to the Soviet Union. He had gone there in August to attend the Conference of the Red International of Labour Unions, Stalin’s state-controlled Trade Union movement.

Communist party officials took him on a tour of mines, factories, and villages and he was impressed by the excellent working conditions he found in the region he visited. The Comer situation was primitive by comparison, and though Russian workers enjoyed little social or political freedom, it seemed clear to him that they fared better in the workplace.

Fired up with idealism and high hopes, Boran set about agitating for pay rises and improved working conditions in Comer. The bosses and their powerful allies hit back on all fronts. Anyone who joined the Miners and Quarry Workers Union would be sacked immediately, they warned, and any man known to be a supporter of Boran’s would be denied employment in the area.

The Parish Priest of Clogh, Father Kavanagh, lashed out at the union. He alleged that Boran had used “Russian Gold from the home of Godless Communism” to finance his activities. Father Coleman of Kilkenny’s Black Abbey rowed in behind the Clogh PP. “Ye’ll get a terrible fright on Judgement Day if ye follow these Communists”, he warned.

Boran defended the union in The Worker’s Voice, asserting that its funds came from the same people who filled the church collection plates at Mass: the poorly-paid miners and their hard-pressed families.

On October 17th, 1932, the union called a strike for higher pay. A crippling economic recession had reduced the miners to a two-day week, resulting in greater hardship for the whole community. For more than a month, they and their loved ones endured severe food shortage and other privations as the pickets persisted…

To be continued…